On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was on a train bound towards Manhattan as terrorist-piloted planes struck the towers of the World Trade Center—my destination. I somehow (foolishly) managed to get to lower Manhattan where I became tangled up in the events of that horrible day. It took me more than 24 hours to get home. This is the (mostly-unaltered) account I wrote in a notebook the following day.

September 12, 2001, 11:55 am.

I should probably write down as much of this as I can before I forget it or my recollection of my day becomes mixed up with the media coverage. It’s probably too late for that last thing…

It’s a beautiful Wednesday. It’s Fiona’s [my daughter’s] first birthday. My father had surgery yesterday. And yesterday, the World Trade Center towers in Manhattan were destroyed. I watched from a rooftop as the North Tower fell. I don’t think I have ever seen anything so awful.

I’m writing this on a train in the Hoboken Terminal, after 24 hours of trying to get home. But I’ll start from the beginning.

Yesterday started out the same as any other day. I got up early with Fiona, who had had a restless night because of her teeth coming in. She’d woken up several times, so Rachael [my wife] and I were both tired.

I made the worst mistake I would make all day that morning. I had started work at a new job the day before and had had to wear a suit for a client meeting. Since the company, Funny Garbage, was hip and funky (if you couldn’t tell from the name), I was determined to wear hip, funky, casual clothes: jeans, a patterned shirt, and my blue shoes. These shoes were not made for walking, just for style. I would end up walking over six miles in them. My feet are killing me now—they are blistered and swollen.

That morning, I also packed up [in a paper bag] a number of personal things to take to work—books, mainly, but also some photos and desk junk. Running to make the 9:00 train, the handle on the bag broke, so I just had to carry it.

The train ride was normal at first until Rachael called me on my cellular phone. “Don’t go to the World Trade Center,” she told me. “Heather [her sister] called from Spain and said a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center.” “Seriously?” I said. I really didn’t believe it. I said I would go uptown instead. I had been planning to go to the WTC [via PATH], then change to the N/R train to get to Funny Garbage, on Spring Street in SoHo. I had too much stuff to carry, I figured.

But then other [passengers’] cell phones kept ringing, and people getting on at other stations were talking about it. We didn’t really know how bad it was until we saw it out the train window. The two towers spewing smoke like two cigarettes. “It’s like a movie,” everyone kept saying. “Jesus Christ,” was what I said when I saw them. [From our vantage point] you could clearly see a giant gaping black hole in the side of the north tower.

We got off the train to panic at the [Hoboken] train station. People were already getting on trains to go home. [Which is exactly what I should have done.] Undeterred and, I guess naively, I walked down to the PATH trains, even though someone said no one could get into Manhattan. I got on a waiting PATH train and amazingly, it went into the city. One Japanese woman, a tourist, asked a man how to get to the World Trade Center. He gently told her that she probably didn’t want to go down there today.

I got off at 9th Street [at 6th Avenue] and immediately saw crowds of people in the street, looking at the towers. Or rather, tower. Only one was standing [the north tower] but I didn’t know that. There was so much smoke you couldn’t see the south tower from my vantage point. It wasn’t there to be seen.

I started the over a mile walk to Spring Street [and Broadway]. People stood in the streets, staring. Some gathered around TVs in street-level apartments or around cars that had their radios on. People were streaming up from downtown [TriBeCa and Wall Street] on foot. I tried calling Rachael, but cell phone service didn’t work. My battery was soon low, so I was forced to turn my phone off.

I made it to my office. Because it was only my second day, I didn’t have any keys. Someone gave me a set, so I was able to unlock the door and get to my desk.

I left my personal stuff at my desk and, finding some stairs, went up onto the roof. There, a few minutes later, I watched the north tower collapse.

I don’t think it’s a sight I will ever forget. The top of the tower started flaking away, chunks of the grid-like outside of the building, then the huge antenna [on the top] tilted then sank, as did the whole top of the structure, into smoke. The sound was like a huge groan and a whoosh as the building vanished. Then there was a moment of absolute silence and all I could see was a stripe of blue sky where the building once was.

Then the gasps and the cries. I was silent, stunned. I was simply dumbstruck. I could not believe what I saw. It seemed like a dream—a horrible dream.

[One thing I’ve remembered since then: I heard someone screaming as the tower collapsed, and it took me a second to realize that it was me.]

The next few hours were spent watching a television that was in the office and trying to figure out how I was going to get home. With the office closing, the bridges and tunnels closed, and no mass transit, I was stuck.

After several phone calls and waiting, I decided to make my way to my friend Sylvia’s apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

[One other memory that has stayed with me from this point in time is the roar of fighter jets flying overhead. To this day, I can’t stand that sound.]

The walk from my office to Sylvia’s was four miles. It was another scene that would have been unimaginable the day before. Thousands of people streaming out of Manhattan on foot over the bridges. I walked over the Manhattan Bridge, one of a sea of humanity. The bridge was closed to traffic, so we walked in the street. The Red Cross was there, handing us water before we got on the bridge.

Where the World Trade Center had been now was only a twisted ruin of metal and stone, throwing up a huge plume of grey and black smoke that curled up over the city and stretched deep into Brooklyn. The cloud of smoke sometimes changed the sun into a burnt orange disk.

As I was midway across the bridge, a loud rumble shook the street and everyone stopped, scared. But it was only a subway passing below us. Fear was like another particle in the air. We were like refugees fleeing from a war-ravaged city. Which, I suppose, we were.

I made it to Sylvia’s and spent the night there along with her brother and sister-in-law who were visiting her from Iowa and had gotten stuck due to the grounding of all airplanes.

This morning, I was able to take a subway, then PATH, then the train home. The faces of my wife and one-year-old daughter were the best things I had ever seen.

[There ends my account of the day.]

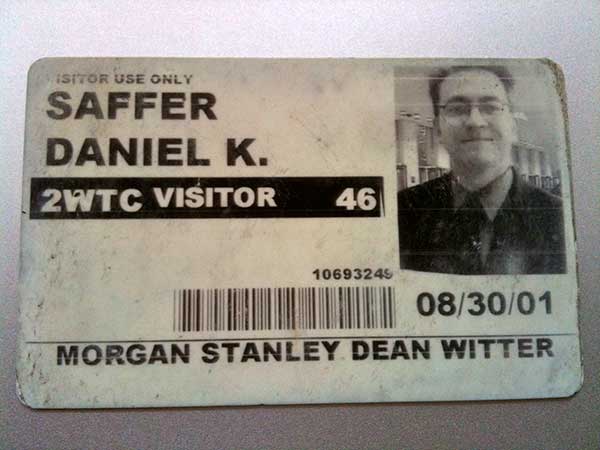

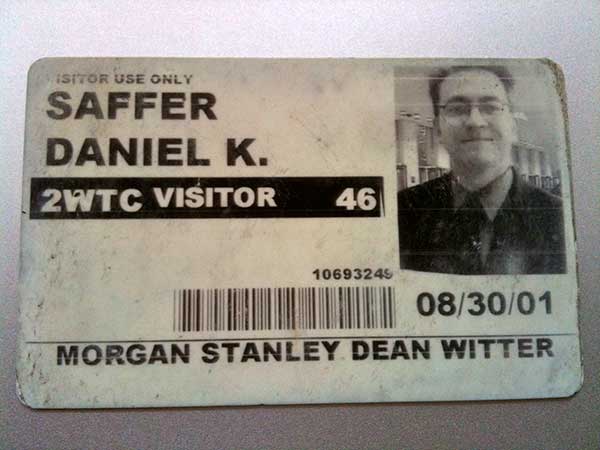

One final anecdote I want to share. I’d been laid off in May 2001 (from my job across the street from the WTC), so that summer, I was interviewing for jobs (including the one I eventually got). One of the jobs I interviewed for was at a company (unfortunately named) Soft and GUI, which did work almost exclusively for Morgan Stanley. Their office was embedded with Morgan Stanley—in the South Tower of the World Trade Center, floor 72 if I remember correctly. Which was directly below where United Airlines Flight 175 struck (floors 77-85). I interviewed there on August 30, and, had I gotten the job, September 10 likely would have been my first day at work. I was even joking about a terrorist attack as I was going through security on August 30, where they snapped this photo. I found this card about three years ago in the bottom of a box:

I carry this card in my wallet now to remind me that life is short and we don’t know when it will end. As much as we all like to imagine ourselves dying at a ripe old age, the truth is you can die today, just doing your usual routine, going to work. That’s the real lesson of 9/11 for me. Things you can see as a disappointment (like not getting that job you interviewed for), can actually save your life. We don’t—can’t—see the Big Picture, but we have to pretend that we do to get through the day. The Big Picture doesn’t care about you or your needs, hopes, and dreams. Occasionally something happens, a 9/11, to remind us of this. But we have to carry on; there’s only one alternative, and that’s not pretty either. After all, the only thing that actually kills us is what kills us. But that could happen today, right now, so make what you’re doing with your life matter. You can’t stop The Big Picture. It keeps moving, drawing an incalculable number of variables together. The only thing to do—the only thing worth doing—is to try to live with meaning, so that if today is the last day of your life, as it was for thousands on September 11, 2001, those who knew you will mourn.

Related Posts